A bird that flies from the ground and lands on an anthill does not know that it is still on the ground.

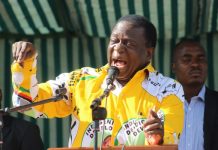

This old African saying summed up the thoughts of many Zimbabweans after going through the list of President Mnangagwa’s first Cabinet. Others invoked a more familiar cliché: the more things change, the more they remain the same.

It’s fair to say that given the high hopes and expectations before the announcement and the long wait for it, many were left underwhelmed by the Cabinet line-up. Zimbabweans were expecting a sea-change from the Mugabe era. After all, had there not been a revolution, or so they thought? Had they not been promised a New Era? Caught up in the euphoria of the moment, they had shut down different and more cautious voices. They chose to believe their own dreams, substituting them for the tough reality of real politics.

Same old faces

Many expected change to be visible in the make-up of the new Cabinet. They expected new faces and fresh ideas. “We need new names,” some said in a witty reference to the title of NoViolet Bulawayo’s award-winning novel. They wanted to see new people running the affairs of the country. But to their disappointment, a lot of the names that feature in the new Cabinet are the same old and tired names they have seen before in Mugabe’s cabinets. Some have been in government for more than 20 years. Unless Mnangagwa has a miraculous formula, it will be hard to teach these old dogs new tricks.

One of the cautionary notes given by some observers when Mugabe was being removed from power was that while the man was on his way out, it remained to be seen whether the system that he had created was also going with him. It would be harder to dismantle this system and the institutional culture built over 37 years. For seasoned watchers of the Zimbabwean political scene, it was hard not to be cautious, given that the authors of Mugabe’s ouster were part of that system. While Mnangagwa has given some positive vibes in his first few days, his choice of Cabinet ministers is a strong reminder that the institutional culture has deep-seated roots. The new President is still unable to see beyond the world and characters that Mugabe created. He has looked to the same characters that failed dismally under Mugabe.

Mnangagwa had hit the right notes in the first few days, declaring an amnesty for those who externalised funds to repatriate them in exchange for immunity from prosecution. It was seen as a first significant step in the anti-corruption drive. When former Finance Minister Chombo was arrested and remanded in custody, many thought that was a show of seriousness. But they wondered if the net would close down on some of the new President’s top allies. They were concerned when they saw suspicious characters who have been accused of corruption surrounding the President. Now, those same characters are key members of his Cabinet. What hope is there that they can ever be prosecuted for their alleged crimes when they control the very ministries that have investigatory powers? This has left many people deflated.

When I asked on social media a few days ago which individuals Zimbabweans did NOT want to see in the new cabinet, four names kept coming up consistently: Obert Mpofu, Patrick Chinamasa, David Parirenyatwa and Lazarus Dokora. All four of them are Mnangagwa’s Cabinet. All hold senior positions – Chinamasa is back at Finance, Mpofu still holds Home Affairs, Parirenyatwa is back at Health and Dokora, much despised for his role as education minister under Mugabe is back in his portfolio. This was Mugabe’s Cabinet, and yet this too is Mnangagwa’s Cabinet. For many Zimbabweans, it’s like they had a beautiful dream in which they owned a mansion only to wake up the reality that they are still sleeping on the mud floor of the their little hut. On these ministerial choices, the new leader seems to have either misread the public mood or he simply doesn’t care much for that opinion.

Boys in uniform

Apart from the disappointing show of continuity, the other significant feature of the new Cabinet is the military appointments, which ironically add credence to the coup theory, which its authors have been desperate to deny. For most observers, this looks like a reward for the military or more specifically, like the military asserting its authority. It goes without saying that the military were the key drivers in the removal of Mugabe and the change of government. The head of Zimbabwe’s Air Force, Air Marshall Perrance Shiri is now a Cabinet Minister. He heads the Lands and Agriculture ministry. There, he will take charge of Command Agriculture, a policy that is based on a command model of economics and was hailed as a success last season. The military was an important player in Command Agriculture, so it is probably not surprising that a top military man has been assigned to that role.

The general who after announcing the military intervention became the face of it locally and internationally, Major General Sibusiso Moyo, is the new Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Trade. This makes him the country’s top diplomat. This also means the face of Zimbabwe’s international relations will be a military man, fitting probably, given the circumstances that gave birth to the new government. The military were the midwives. Mugabe often appointed men with an academic background to that post, with Nathan Shamuyarira and Stanislaus Mudenge being two of his stand out appointments of that pedigree. Mnangagwa had three former diplomats to choose from: Mumbengegwi, Mutsvangwa and Khaya Moyo and to exclude all in favour of a man from the military is an interesting and intriguing choice which probably suggests that the military had a strong hand in it.

This is new territory for Major General Moyo, who must now shed off his military fatigues for diplomatic robes as he embarks on the tough road of re-engagement with the international community. Does the appointment of a military general signal a hard-nosed approach to foreign policy? Moyo exhibited a firm but calm and reasonable demeanour when he spoke. Announcing a half-coup is one thing, navigating the murky waters of international relations is another, as his immediate predecessor, Walter Mzembi found out in his very brief tenure. It will be interesting to see how he carries himself in that demanding and important role.

It is important to note however, that these appointments of military personnel are not an entirely new phenomenon. Former servicemen have served in government before, but usually after they have retired. Generally, the movement of retired generals to civilian roles has some history with many such officers occupying several civilian roles including at institutions like the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission. Nevertheless, given the immediate context, it is hard not to see them as an acknowledgement of the role of if not a show of the influence of the military in the aftermath of the military intervention. They also come just a day after a number of officers in the military were promoted. One interpretation is that this is a reward for the military’s contribution in the change of government. With a strong presence of the military, some may characterise it as a Command Cabinet.

Gender imbalance

The 2013 Constitution requires the President to take into consideration issues of regional and gender balance in his appointment of Cabinet Ministers. Mugabe did not pay much attention to the call for gender balance and it seems his successors has found it difficult to take a different path. There are only three women in Cabinet – Oppah Muchinguri who returns to Environment and Tourism, Sithembiso Nyoni who is now Minister of Women and Youth Affairs and Prisca Mupfumira who is now at Tourism and Hospitality. It’s a glorious return to Cabinet for Mupfumira who was fired by Mugabe in his last reshuffle. Women will not be pleased by this continued exclusion from powerful roles.

Merging ministries

One positive is that by merging some of the ministries, Mnangagwa has to some extent reduced the size Cabinet although as shown below some of the moves dilute this development. Foreign Affairs has been merged with Trade, while Women and Youth Affairs have also been merged. Defence Security and War Veterans have also seen a merger of formerly three ministries, which makes sense. There are also fewer Deputy Ministers, although he really should have done away with that burden altogether. In the past, Deputy Ministers were not even able to act in the absence of their substantive ministers, which left many wondering why they held the posts in the first place. They are an expensive waste and should be done away with. The country is broke and does not need Deputy Ministers. Some would argue that they have been kept for political reasons – to create jobs for the boys.

Provincial Ministers

Regrettably, just like Mugabe before him, Mnangagwa has retained provincial governors, who are presented under the façade of Ministers of State for Provinces. There are 10 of them - 8 for the provinces and 2 for the metropolitan provinces of Harare and Bulawayo. The new Constitution had done away with the posts of provincial governors, opting for provincial chairpersons who are supposed to head devolved provincial councils. Mugabe circumvented this, ignoring the entire devolution chapter and appointing governors under the guise of Minister of State. One would have hoped that his successor who take a different turn. Instead, he has chosen to walk exactly the same path. These ministers are useless unless they are heading a devolved structure. It doesn’t help that he has also retained the same faces in that role, such as Miriam Chikukwa and Martin Dinha. It’s an expensive waste for the taxpayer but they will fulfil a political purpose as the president’s gatekeepers in the provinces.

The annihilation of the G40 faction was expected, with most of the members that were aligned to Grace Mugabe removed. Mzembi was Foreign Affairs Minister for less than a month and the highlight of that was Mugabe’s humiliation when he was appointed and removed as Goodwill Ambassador for the World Health Organisation. Professor Jonathan Moyo, Patrick Zhuwao and Saviour Kasukuwere were always going to lose their jobs so there is nothing surprising there. Gone also are Walter Chidhakwa, a relative of Mugabe and Edgar Mbwembwe who also held post at Tourism for less than a month. Chombo who was Finance Minister is in remand prison facing a raft of corruption charges. Sekeramayi, who G40 touted as a counter-weight against Mnangagwa during the succession race has been dropped from Cabinet for the first time since 1980 unless he is earmarked for the Vice President’s role, which seems unlikely. A surprise inclusion in Mnangagwa’s Cabinet is Michael Bimha, who is a relative of Grace Mugabe but retains his role at Industry and Enterprise Development. Supa Mandiwanzira, another said to be connected to the Mugabe family by marriage also retains his post as ICT Minister, which now includes cybersecurity. Perhaps Mnangagwa wants to portray that he is not necessarily driven by vengeance.

Reward for allies

It would have been surprising if Mnangagwa had not rewarded staunch loyalists. There were men and women who stood by him through thick and thin, becoming casualties of the Mugabes vengeance in the process. They include July Moyo, Chris Mutsvangwa, his wife Monica, Victor Matemadanda the War Veterans’ Secretary General who openly challenged Grace Mugabe when it was still dangerous to do so, Josiah Hungwe and Owen Ncube, a staunch ally in the Midlands province and Pupurayi Togarepi, who became a victim of the factional wars when he was replaced by Kudzanayi Chipanga as head of the Youth League. All are rewarded with ministerial portfolios. Mnangagwa knows he has an election in less than 12 months. It would be foolish to disappoint his allies who bear scars of defending him. A surprise omission in this regard is young politician Justice Mayor Wadyajena, the Gokwe MP who stood with and defended Mnangagwa even in the darkest times. But this Cabinet is devoid of young blood and the youths will be disappointed.

Another expensive waste

Zimbabweans had thought that this would be a new era in which mere departments would not be elevated into Ministries. They will be happy to note that there is no more psychomotor ministry which Josiah Hungwe held but has nothing to for it after 4 years in office. However, they will be disappointed to note that old habits die hard, given that Chris Mushohwe retains his Ministry of Government Scholarships, which Mugabe created for the same man only a few weeks ago. It’s hard to see why the administration of government scholarships requires a whole Minister. It is a department in one of the education ministries which can be headed by a director. For the new president to retain a ministry that was created for Mugabe to accommodate a demoted minister represents the kind of continuity that many people were hoping would give way to radical change. It militates against the message of change and cost-saving that the new president has been preaching.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the new Cabinet is not what most people expected. There is a sprinkling of new faces but hardly enough to dilute the same old faces from the Mugabe era. They were tired of these faces. As it is, it reads like a reshuffled Mugabe Cabinet, with a few odd names added into the mx. People had high hopes that the so-called “New Era” would represent a brave new world in which appointments would be based largely on competence ahead of patronage and loyalty alone. The buzzwords in the last few days were “technocrats” and “meritocracy”. These hopes have not been fulfilled. Mnangagwa was obviously looking at his campaign for elections. He needs to keep the team that propelled him to top of the food chain. He has rewarded them. It will be interesting to see who his choices for the Vice Presidents’ posts will be.

If his international allies pour in resources, he might just be able to charm the nation with some quick wins in the economy, his questionable Cabinet choices notwithstanding. He will hope that he gets a substantive term where, perhaps, he will have more freedom and leeway to make more courageous appointments. On this occasion, he has gone for a safety-first approach rewarding loyalists and old allies. He has underestimated the voice of young people. There is a new generation that had taken a liking to his entrance after Mugabe’s removal. Yet there are no young people in his Cabinet with whom they can identify. It is a Cabinet of old people, many of whom have been part of government furniture for far too long. Their presence in government does very little to inspire the young people.

WaMagaisa