Everywhere you look, there is back-stabbing, defections, grandstanding and chaos. Joel Konopo looks at the disjointed state of politics in Botswana as the election nears.

Under intense heat, atoms tend to fly uncontrollably. Such is the state of Botswana’s political parties as the country nervously gears up for elections in October this year.

The ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) is convulsed by the worst internal crisis in its 50-year history, reflecting a potential shift of power to the opposition in a country where a single party has always held sway.

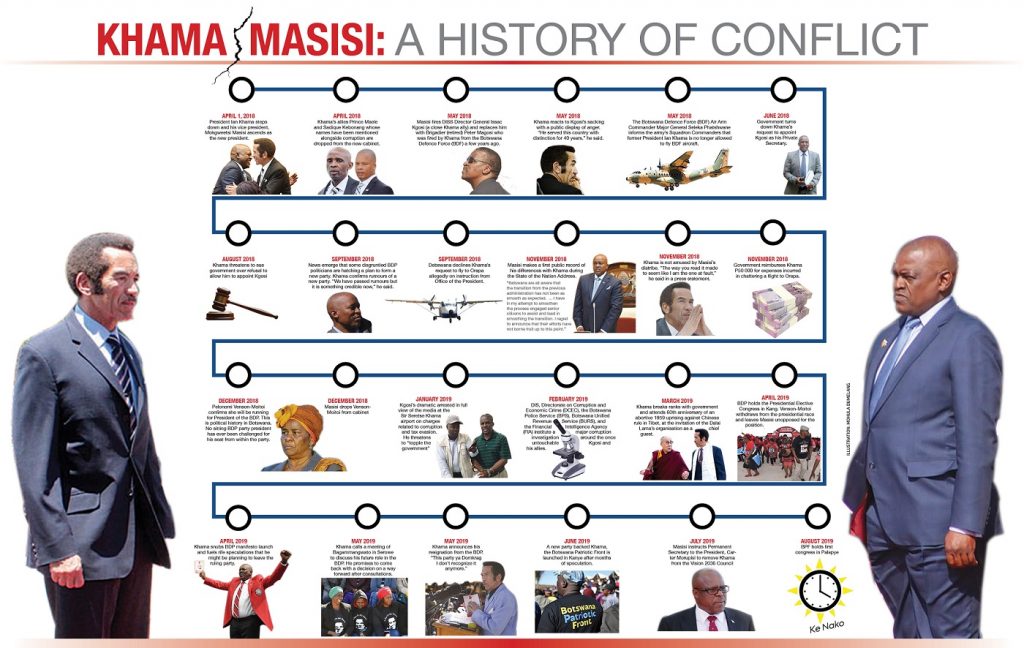

Presumably after backroom discussions, former president Ian Khama handed power to his hand-picked successor, Mokgweetsi Masisi, on April 1 last year.

It is a choice he has come to regret – Masisi immediately escaped his predecessor’s shackles and struck out on his own.

Angering Khama, the new leader sacked two of his long-time allies; the country’s head of intelligence, retired colonel Isaac Kgosi, and Roy Blackbeard, Botswana’s High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, who had been in London for 20 years.

Kgosi had been Khama’s batman during the latter’s stint as army chief and joined the public service when Khama became vice-president.

In 2008 he became the founding director-general of the dreaded Directorate of Intelligence and Security Services, which was soon embroiled in allegations of extra-judicial killings.

Blackbeard resigned as an MP to pave the way for Khama when he joined politics in 1998, and was rewarded with a permanent ambassadorial role in the UK.

Masisi also rolled back some of Khama’s pet projects, lifting a ban on hunting and scrapping part of his controversial alcohol levy.

What is clear is that Khama’s resentment of Masisi is born out of a realization that he cannot pull the strings behind his presumed loyalist.

The puppet-master’s ploy worked well for Vladimir Putin in Russia, where Dmitry Medvedev kept the president’s seat warm for him.

But such tactics may be less effective in Africa: Angola’s Edwardo de Santos has also found himself sidelined by his successor.

In an interview with the SABC, an incensed Khama objected: “He [Masisi] is immature and intolerant … I have come to realize that maybe I have misjudged [him].”

During his term in office between 2008 and 2018, Khama’s disdain for the independent media was apparent. He now tours media houses drumming up support for Masisi’s removal from office.

To show his anger at his successor, who he says is “not doing a good enough job”, Khama has joined forces with other disgruntled BDP cadres to form an opposition party, the Botswana Patriotic Front (BPF), that is loosely allied with the main opposition grouping, Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC).

The two parties have little in common: Khama’s BPF is driven mainly by personal pique and has no clear ideological stance, while the UDC is broadly social democratic.

One could argue that a vigorous opposition coalition is vital, particularly given the ticking time bomb of youth unemployment in Botswana, which stubbornly remains one of the highest in the region.

Whether the BPF-UDC front fits the bill is another question.

How did a country that had become a byword for stable democratic rule and national unity in Africa fall prey to such bitter infighting? The BDP’s implosion has to be seen as a willful failure of the automatic succession that has benefited the party for more than five decades.

There is a school of thought that Khama – the son of Botswana’s founding president, Sir Seretse Khama – tried to strong-arm Masisi into picking his younger brother, Tshekedi Khama, as his vice president. Both Masisi and Khama deny the claim.

Tshekedi remains in Masisi’s cabinet, although demoted from the economically important portfolio of wildlife, tourism and natural resources to the less prestigious one of youth employment, sports and culture development.

Khama’s defection will hurt the BDP, as Khama has the advantage of name recognition and the broad appeal needed for the party to be assured of an election victory.

There is a certain right to rule associated with Khama, who is also paramount chief of Bangwato tribe in central Botswana, a BDP stronghold.

There is a historical tribal connotation to Ngwato hegemonic control of the BDP. In the last general election, the party won all the 19 constituencies in the central region, representing a third of Botswana parliament.

This trend is unlikely to continue, as Khama supporters and village elders in the central region are divided on who to back.

At first glance, is surprising to see the leader of the opposition UDC, Duma Boko, ingratiating himself with the 66-year-old former army general. In the past he has been a fierce Khama critic. (See sidebar)

“We never had a personal problem with him,” Boko told the Duma FM radio station recently. “It was the BDP that we differed with.” He told the BBC in May: “If he [Khama] is prepared to support this new narrative of Botswana, then we will work with him.”

He is being disingenuous. He previously said his coalition of three political parties; Botswana Congress Party, Botswana People’s Party and Botswana National Front, would prosecute Khama and Kgosi for corruption on a grand scale.

In the past, he accused Khama of systematically killing his political opponents, including the UDC’s first secretary-general, Gomolemo Motswaledi, who died in a car crash in July 2014.

The UDC has the scent of power in its nostrils. It is positively drooling over the attention it is getting from being linked to Khama and his new party.

The battle with Khama has distracted Masisi, too. His priorities on taking the helm should have been to fix weak oversight institutions, re-establish better public finance discipline and embark on a large-scale job creation.

Alas, he has never bothered himself with these tiresome and bureaucratic concerns. His conduct over the past 14 months points to a man with a focus problem.

On the campaign trail, his policy platform has been lamentable. Recently he was left with egg on his face after backing an outrageous opposition campaign message that it would create 100 000 jobs within a year.

He also has a weak and uninspiring running mate in the aptly named Slumber Tsogwane, who has little chance of retaining his Boteti West constituency in October. In the 2014 general election, Tsogwane beat the UDC candidate by a tantalizingly narrow margin.

Other fairytale promises made by Masisi include designing an electric car in Botswana. That would require an innovative culture and entrepreneurial spirit, both notably lacking in the country.

Botswana’s Ease of Doing Business index deteriorated last year compared to 2017, according to this year’s World Bank’s Report.

The electorate expects concrete and realistic propositions from Masisi, especially geared towards improving livelihoods.

However, to his credit, he has done few things right. Withdrawing the much-contested electronic voting machines – which the opposition complained could be manipulated in favour of the BDP – was an act of bravery.

Masisi has also attempted to reposition Botswana in the global arena after 10 years of Khama’s inward-looking policies. For example, he has improved Botswana’s relations with China and the African Union.

During his term in office, Khama skipped most high-level United Nations and AU meetings, saying they would clash with scheduled domestic arrangements.

But there is an increasing sense that this is a President of words, not deeds.

Fourteen months into office, the former educator has yet to draw up a roadmap, giving an indication of how he intends to address sustainable long-term economic growth, or to promote broad-based economic diversification in a country overwhelmingly dominated by mining and tourism.

He must deal with the declining quality of education, reform weak oversight institutions, build citizens’ economic empowerment and fight institutionalized corruption.

By now Masisi should have heeded the calls by economists to address the deteriorating quality of public financial management and remedy poor spending and increasing levels of public sector waste and inefficiency.

The watchdog agencies he inherited – the Directorate on Intelligence Services, the Financial Intelligence Agency and the Directorate on Corruption and Economic Crime –are black holes in which corruption has proliferated over the past 10 years.

More than a year later, Masisi has done nothing concrete to reform those institutions.

He is also implicated in corruption. Last year, the president was tainted by corruption scandals in the National Petroleum Fund and Capital Management Botswana, with accusations that he was one of the top political figures who had directly benefited from their irregular deals.

While there has been a noticeable change from the previous administration in the way he relates with the media and trade unions, Masisi still falls short in keeping his promises of an open and transparent government.

He has remained mum on plans to promote media freedom, despite a campaign to repeal the Media Practitioners Act of 2008, largely seen as intended to restrict and intimidate journalists.

Overburdened nurses and teachers need an urgent and imaginative response, as opposed to the current rhetoric. Youth unemployment exceeds 40% and much of the economy is in foreign hands.

There are also concerns about nepotism in the civil service.

Many Batswana are desperately poor, despite the country’s obvious wealth. With radically improved economic management, their lot could improve – but only if Masisi starts to focus on the country’s real problems.

Is Boko electable?

For many young Batswana who want change, Umbrella for Democratic Change leader Duma Boko is a pillar of hope.

Boko has managed to re-energize the opposition and is generating much hype among young voters. He has public appeal, charm and rhetorical skill.

Hope is easy to sell because, after 10 years of Khama’s paternalistic politics, the masses are yearning for what is tantalizingly held by a minority – the long-established landowners who have benefited from BDP misrule.

The UDC manifesto sells hope: it has grand reformist ideas, but does little to back them up with sound economic projections.

It has, for example, promised to create 100 000 jobs and introduce a living wage of P3 000 a month in the first 12 months of his government, but provides no insight into how the various economic sectors will create employment and how much this will cost the economy.

Some of his promises are plain populist – such as tripling the old age pension to P1 500 a month and the student allowance by 56% to P2 500. Under a UDC government, the 38 000 government-sponsored tertiary school students would cost not far off a billion pula a year

It currently costs government P63-million a month to pay 117 871 old-age pensioners , according information from department of social security. Under the UDC, the government would pay P2.1-billion a year.

A former government auditor interviewed by the INK Centre for Investigative Journalism, who did not want to be identified, said he feared that UDC economic plans would increase the wage bill by up to 40%.

Boko’s conduct of his own affairs does not inspire confidence. He has been accused of not paying child maintenance and honoring his tax obligations.

He has also been linked to shady South African business people, including the controversial businessman, Malcom X.

But if you are a young unemployed person, angry at the current government and yearning for change, you might be inspired to vote for this Harvard-educated lawyer and his party.

Potential spoilers in opposition ranks are the liberal-democratic Alliance for Progressives (AP) and Botswana Movement for Democracy (BMD).

The AP likes to think of itself as the party of economic competence. It’s leader, Ndaba Gaolathe, a graduate of the Pennsylvania-based business school Wharton, has at least a clear vision for the economy.

Gaolathe’s father was governor of the central bank and finance minister under former president Festus Mogae.

His defining ideas have been fiscal rectitude, cutting spending and slightly raising taxes to contain public debt.

The AP has no popular base and has not been tested – but it might emerge as a splinter party that denies the UDC outright majority.

BMD is led by criminal lawyer Sidney Pilane. Nicknamed “the warthog” in political circles, Pilane is currently challenging the BMD’s largely unexplained expulsion from the UDC coalition.

But his party has lost most of its key members to the BDP and UDC, and its court battle may not save “the warthog” from political extinction.

A Masisi victory in October will be Khama’s downfall. Zambian president, Fredrick Chiluba was effectively the author of his own downfall when he anointed his successor, Levy Mwanawasa.

But his major hurdle is not Khama the man, Boko or the lesser opposition parties. It is the Ngwato hegemony in central Botswana.

Additional reporting by Kago Komane

INK Centre for Investigative Journalism, a non-profit newsroom carryout out investigative journalism in the public interest produced this story.